So, I was trolling the web today, looking at this and that, and I chanced upon this New York Times piece. It's the final entry in a blog series that the Times commissioned from Douglas Coupland, and if you haven't read it already, or even if you have, it's worth a look.

(Now, the problem with this piece is that you have to have signed up for the Times's subscription-only "Times Select" service to read it. The good news is that the paper is running a brief promotion allowing people a free two-week trial of the service. The bad news is that the sign-up process is a pain in the ass and involves having to provide your credit card information and then keep track of the time so you can renege on day thirteen. And here's the thing about that whole rigamarole: it's not that I even really mind jumping through a few extra hoops to get at some nifty content. It's the fact that the Times and I are forced to lie to each other throughout the process. I pretend that I'm actually considering taking out a paid subscription, which we both know I'm not, and they pretend that this isn't a borderline negative-optioning cash grab designed to get a few bucks out of people who forget to keep track of how quickly fourteen days can pass. Life is already duplicitous enough. Et tu, New York Times? Et tu?)

Be that as it may, it's a neat piece. Entitled "Insects," it contains Coupland's trademark ruminations -- both informative and irreverent -- on the subject of paper, from the paper shortage of the 1980s to the paper that wasps and other insects create to use their nests.

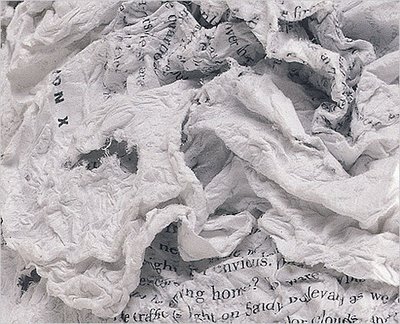

So back to pulp. Back to paper. My cousin in Ontario is an entomologist, and so I think about insects more than I might think about them otherwise. I got to thinking about how wasps and hornets make paper, too, and paper is, in its own way, just as vital to the survival of their species as it is for us. What if you could trick wasps into using human paper to make their own paper? What if you took a stack of Finnegan’s Wakes and pulped them with hot water and corn syrup and left the whole thing in a pasture and let wasps come and gather the cellulose to make nests? What if you added pigment to the chopped up paper, and tricked the wasps into making nests in designer pastel shades — in candy stripes or tie-dyed patterns?You get the gist. Over the course of four weeks, at the rate of one book a week, Coupland masticated several of his novels and used the pulp to create nest-type sculptures. The above is as much as I can copy and paste (from what is a very, very long piece, just so you know) in good conscience. Well, that and a couple of pictures.

...

Nests are beautiful objects — the inner combs in Koolhaasian layers, the striations of pulp that resemble avant garde Japanese fabrics. You can easily meditate on one for hours. (BTW, here’s another thing about nests: they can really stink after being in a shipping box for two weeks. Each day we learn something new.)

So after my nest meditations I took copies of my own novels and began pulping them myself, chew by chew, a slow, laborious process. Have you ever chewed a book? I doubt it. The first thing you need to know is that doing so really trashes your saliva ducts, and it takes about a week to get through one average-size book. The second thing to remember is to drink lots of water and spit regularly or your teeth will turn gray. Usually I’d chew while watching “Law & Order.” (I’m an addict.)

Oh, okay, one more brief excerpt:

To look at my own complete wasp nests raises odd issues in my head and, I hope, in the minds of observers. Is our bunkered mentality about the sanctity of books more genetic than cultural? Are we no different than wasps defending against intruders when we force students to read Henry James or Nadine Gordimer? What would wasps make of books? How do wasps think of their role within evolutionary time? Do wasps have any sense of culture? Why does it feel so strange to see a book removed from our own sense of history and culture and inserted into a non-cultural slot where art or music or any other art form don’t exist?When you read this last bit, it's hard to get a sense of whether Coupland is serious or not, or whether this even matters. What's important is that here -- in the twenty-first century, in the western world -- a widely reknowned writer spent a month chewing a book and thinking about bugs. These are truly great times in which we live.

1 comment:

It's high time a use was found for his novels.

Post a Comment